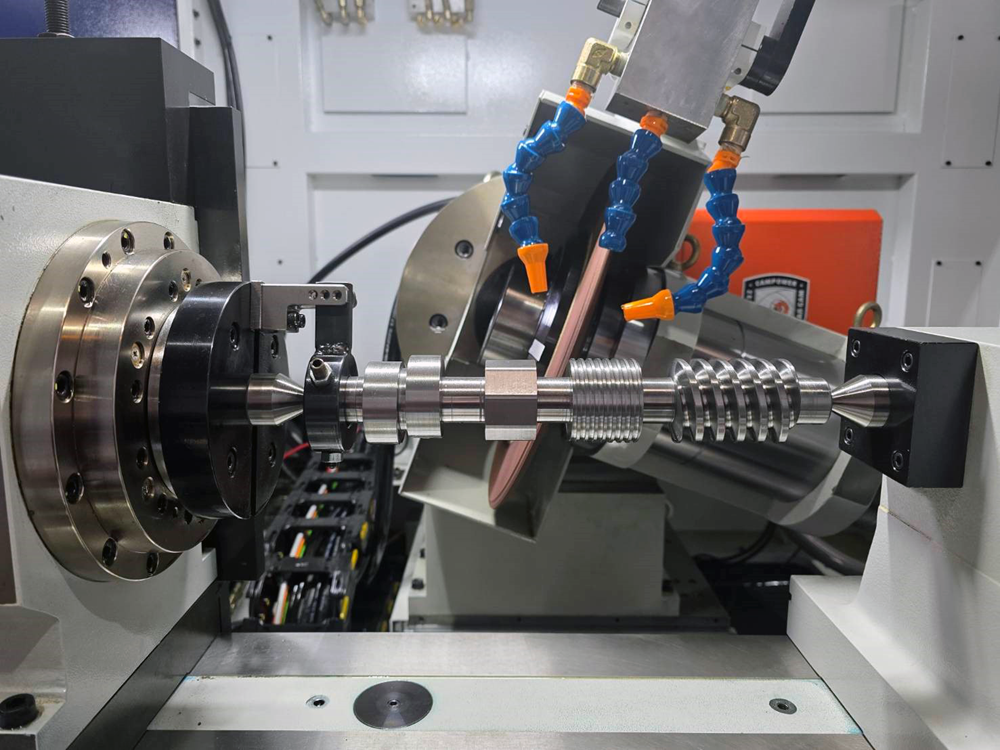

In a world where precision determines success or failure, Mitsubishi Electric says it is setting new standards in wire EDM with the company’s latest MX900 series. What makes this machine special is not just its accuracy of less than 1 µm – it is the combination of advanced technologies that make this precision possible in the first place.

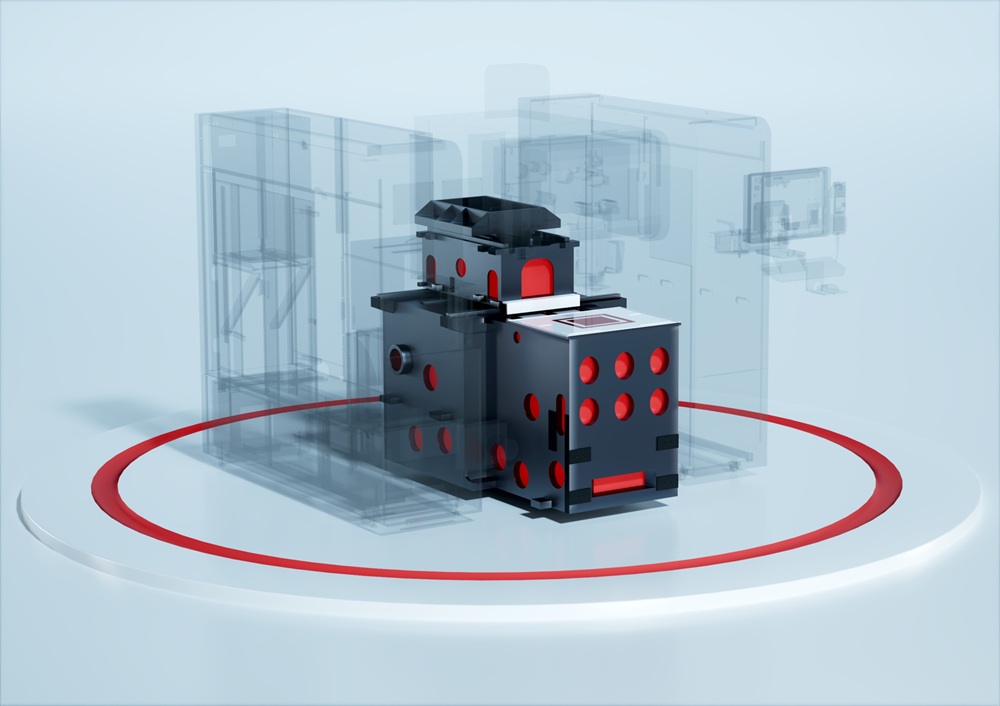

The heart of the MX900 is its well-thought-out gantry design, where the massive machine bed made of spheroidal cast iron is completely decoupled from all peripheral units. This innovation virtually eliminates all vibrations and thermal influences. The eight-fold mounted linear guides with precisely executed mounting surfaces ensure smoothness and virtually no running resistance.

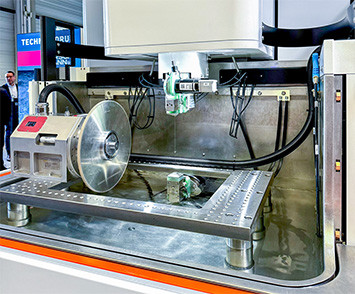

Tubular direct drive technology operates completely contactless and is therefore wear-free. It converts electrical energy directly into motion – without mechanical intermediate stages. Unlike conventional drives, there is no disruptive cogging torque that could impair precision. Communication takes place via polymer fibre optic cables, enabling 400% faster data transmission. The result: positioning accuracies below ±1 µm over the entire travel path – Mitsubishi Electric provides a 12-year manufacturer‘s warranty on this precision.

The MX900 thinks thermally ahead: even before heat can develop, the machine compensates accordingly. The sophisticated two-column concept combines the physical decoupling of heat sources such as pumps and aggregates with predictive temperature control. This forward-looking strategy is crucial, as thermodynamic processes exhibit a certain inertia – pure reactive adjustment would come too late for the required accuracies.

Mitsubishi’s newly developed nPV (Nano Pulse V-Power) generator works with pulses in the nanosecond range and produces a uniform, controlled spark pattern across the entire erosion path. This enables surface qualities up to Ra 0.04 µm in carbide and below Ra 0.06 µm in steel.

More information www.mitsubishielectric-edm.eu